By Avalon Fotheringham, Curator of South Asian Textiles & Dress at the V&A Museum.

Over two hundred years ago, skilled artisans working along India’s southeast coast laboriously crafted gardens on cloth. Working on a finely woven cotton ground, they drew each flower by hand using a mix of mordants, wax, and natural dyes. A speciality of the Southeast Indian ‘Coromandel’ coast, over the eighteenth century global fashions for brightly coloured Indian cottons saw these floral ‘chintz’ fabrics (anglicised from the Hindi ‘chint’, meaning spotted or sprayed) exported all over the world.

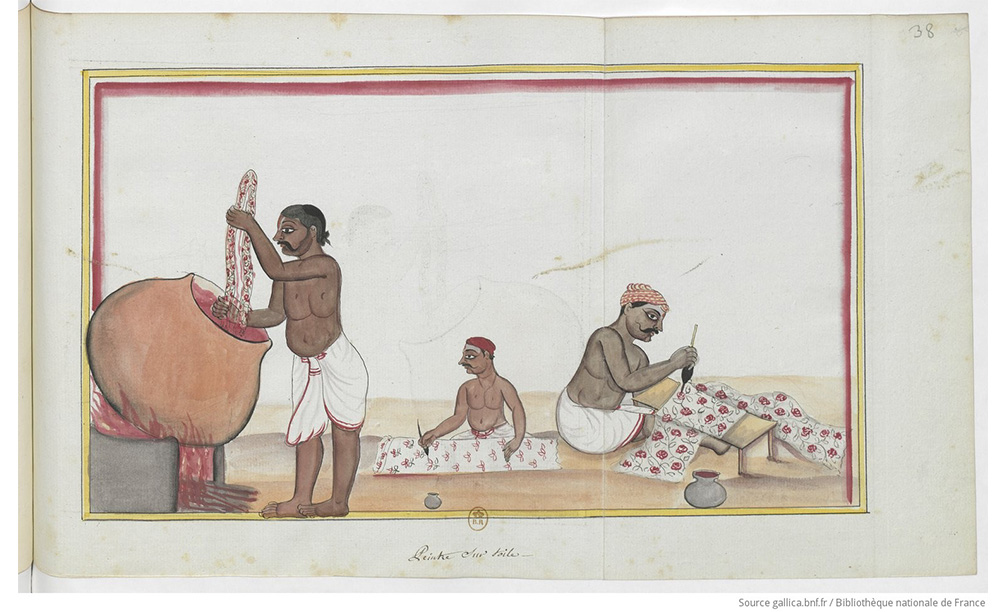

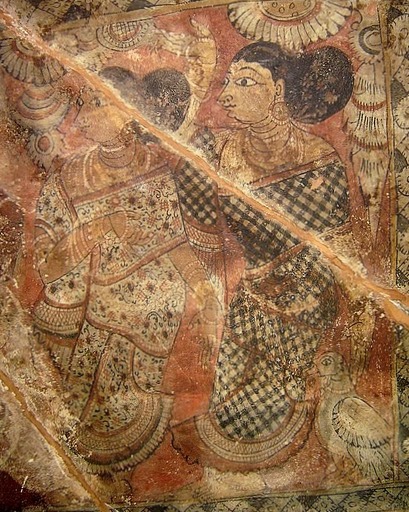

From an album of paintings made by the artist Svami in Madras, India, 1780

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, 4-OD-46 (A)

The patterns of these chintz fabrics were no less international than their markets. The flowers which decorated them combined a mix of both local South Indian and exotic foreign plant species to create marvellous bouquets. Chintz patterns and drawing styles likewise reflected its global popularity. Chintz artisans skillfully fused local South Indian floral pattern formats, motifs and aesthetics with those drawn from wider Indian, Middle Eastern, Chinese, Southeast Asian and European sources. They excelled in the creative sampling and re-styling of design influences, combining and customising seemingly disparate approaches to create new kinds of pattern. In producing and exporting these new patterns, coastal Southeast India played a pivotal role in eighteenth century global fashion as an extraordinarily influential centre of design innovation.

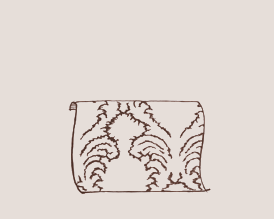

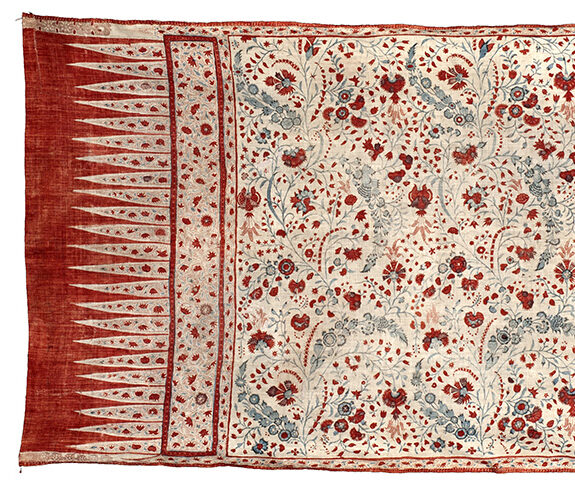

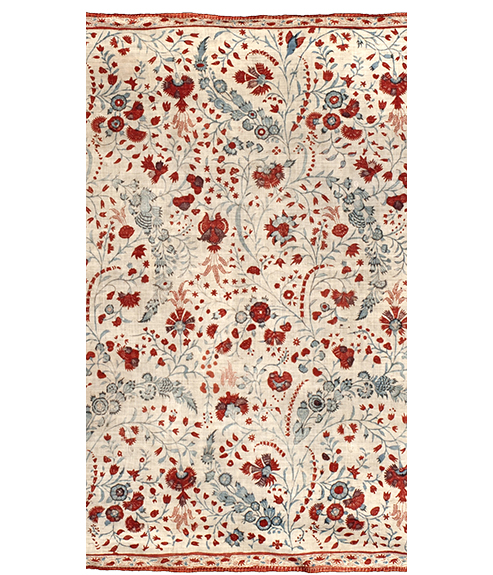

Coastal Southeast India, late 18th – early 19th century

Karun Thakar Collection

Coastal Southeast India, c.1700-1750

Karun Thakar Collection

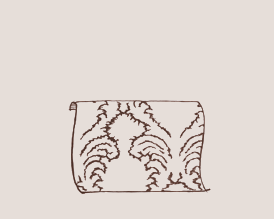

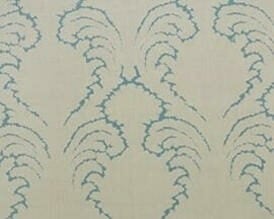

Inspired by the patterns decorating two eighteenth century Indonesian- and Sri Lankan-market chintz skirt cloths in the collection of Karun Thakar, both Soane’s ‘Coromandel Tulip’ and ‘Dianthus Chintz’ designs reflect this story of South Indian skill and creativity.

Both the skirt cloths are patterned using a classical South Indian floral arrangement of blooms strewn loosely across an unoriented field, but heavily reference European floral aesthetics in the style of their floral drawing.

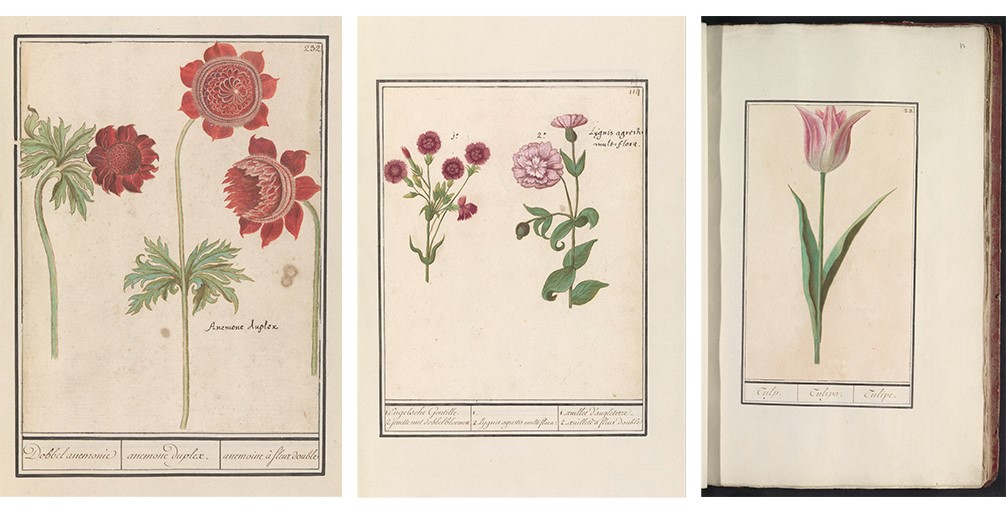

From an album of paintings by the artists Anselmus Boëtius de Boodt and Elias Verhulst

Made in Prague and Delft, between 1596 and 1610

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; On loan from a private collection

Designed and engraved by the artist Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer in France, 17th century Metropolitan Museum of Art; Rogers Fund, 1920

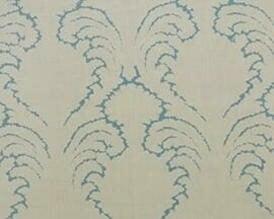

The international array of flowers seen in the ‘Coromandel Tulip’ design includes jasmine, double anemones, dianthus, and larger-than-life tulips,* the naturalistic-style of which suggests the influence of European botanical drawing.

Minneapolis Museum of Art; Gift of Mrs. Stanley Hawks

Similarly, the flowerheads of the ‘Dianthus Chintz’ design are framed by curiously lace-like fronds, likely inspired by the popular scrolling boughs seen in French bizarre silks of the early eighteenth century. Yet neither design is imitative; rather, their artisans used the European naturalistic style to create something new – a fantastic multiplicity of blooms which miraculously grow from shared stems.

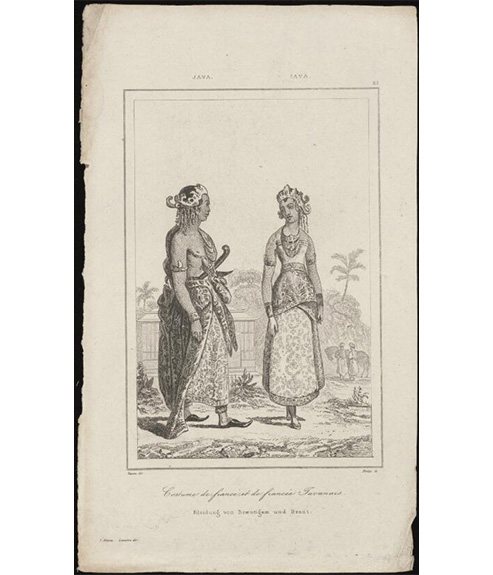

By the artist Claude-Francois Fortier, published in Paris, France, 1836 National Library of Australia

Formatted for wear tied around the waist, the drape and movement of both skirt cloths would have given subtle life to their blossoms, swaying like vines in a gentle breeze. The life-like qualities of their patterns would have been all the more enhanced by their plant-derived colours; reds drawn from chay, yellows from turmeric, and blues from indigo, among other South Indian natural dye sources. While capable of astonishing vibrance in the hands of master dyers, the organic origins of these dyes ensured that the colours of the flowers drawn with them retained a naturalistic realism. This naturalism is echoed in Soane’s entirely new ‘Walnut & Neel’ colourway for the ‘Coromandel Tulip’ design – neel from the Hindi for indigo, a nod to the Indian inspiration behind both the pattern’s design and its colours.

Although over two hundred years old, these gardens of chintz still retain their allure – a testament to the creativity and skill of their artisans. Ever on the point of unfolding its petals, the Coromandel Tulip blooms eternally, as fresh as the day it was drawn.

*I am grateful to Deepthi Murali and Aditi Khare for their expert assistance in identifying these flower species.