In the depths of winter, the swans in London’s Royal Parks take centre stage, white sculptural forms gracing the frosted landscape. They bring life to the icy ponds as they dip their necks, unfurl breathtakingly large wings (they span up to 2.5 metres) and waggle tail feathers, seemingly uninhibited by the human audience. It’s swan season at the ballet too. The English National Ballet’s January run of Swan Lake closes only to be followed by the opening in February of The Royal Ballet‘s production. An opportunity to be swept away by an entire corps of cygnets and Tchaikovsky’s stirring score never ceases to entice – the Royal Opera House performances sell out year after year.

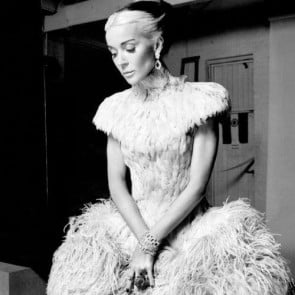

The dancers seem to have a natural affinity to the swans they emulate: slender and graceful, yet with incredible strength. Watching the corps de ballet in the Royal Opera House behind the scenes footage reveals the intense physical demands of a Swan Lake performance, whilst the trailer gives glimpses of the atmospheric stage sets on which the dazzling white costumed ballerinas suspend belief. For a more avant-garde interpretation of swans, we also have the ‘Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty’ exhibition to look forward to, opening at The Victora & Albert Museum on 14th March. McQueen’s final collections saw fabulous gowns metamorphosise models into otherworldly half human half swan creatures.

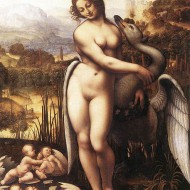

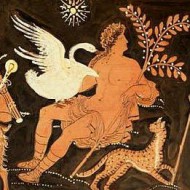

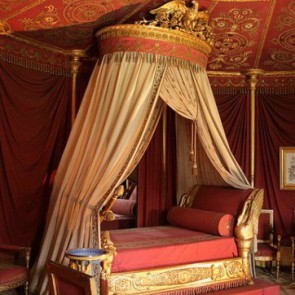

One of the world’s oldest surviving bird species, swans appear strongly in Greek mythology, most notably when Leda is seduced by Zeus in the form of a swan – a legend that has inspired many classical paintings and sculpture. The swan was also a sacred bird of Apollo, coming to symbolise love – for its habit of taking a partner for life – and light. Swans stir devotion in mortals too. Napoléon’s great love and Empress Joséphine took the swan as her emblem. She kept black swans in the beautifully tended gardens of her home Château de Malmaison and slept in a tented chamber surrounded by swan themed furnishings.

In the early 1800s, the Empire style emerged in France, with architecture, decorative arts and fashion drawing influence from Ancient Egypt and Imperial Rome. Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine were the leading neoclassical architects and interior designers of the day, creating furniture and decoration using ancient motifs (such as laurel wreaths), as well as stately creatures (such as sphinxes and winged lions), as symbolic references to Napoléon’s imperial reign. They were engaged to renovate Malmaison, including Joséphine’s rooms which trumpeted her stately swan emblem. Here there was a gilded lit en bateau with great carved swans at its head, chairs with curved arms that took the form of white swans and a carpet encircled with swan motifs. Still intact and open to the public today, it’s pure fantasy.

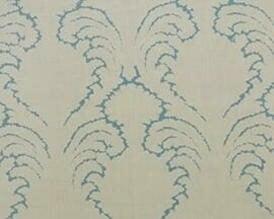

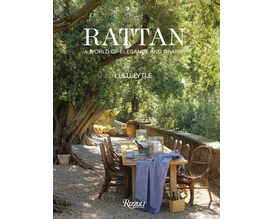

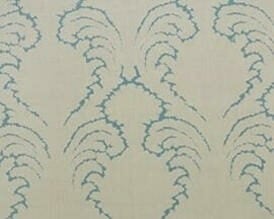

At Soane we’re easily charmed by swans and recall fondly the huge rattan swan that presided in the Pimlico Road shop a few years ago (see the top rotating gallery for a photograph). It came from an early twentieth century Swedish fairground ride and completely captivated Lulu and her children who delighted in sitting within its wings. Swans have inevitably found a way into Lulu’s work – though in a less literal way than that of the Empire furniture designers! Soane’s Cygnet Wall Light and Rattan Cygnet Wall Light have a beautifully curved design inspired by the elegant swan’s neck, while The Cygnet Table Lamp is straight but with similarly pleasing proportions. Highly lacquered in a choice of metal finishes, we like to think these gleaming lights capture something of the swan’s winning looks.

We have started a ‘Birds’ board on Soane Britain’s Pinterest

Top image gallery: Image of The Royal Ballet’s Swan Lake ©ROH / Bill Cooper, 2011; Image of London swans by Kyle Taylor via Flickr; Image of early 20th century rattan swan by Soane Britain; image of The Cygnet Wall Light on Seaweed Wallpaper by Soane Britain.